As the COVID-19 pandemic enters a new phase mitigated by vaccination, it’s time to start asking how we can use innovative responses to address public health challenges and the resulting economic impacts they have. What have we learned from our experience with COVID-19? What could we put in place to continuously monitor existing diseases and quickly look for emerging diseases? How can we rethink economic stimulus delivery to vulnerable populations?

How can we track emerging diseases in new ways?

Let’s first look at ways that we might understand more about emerging diseases. Many of our public health colleagues are discussing needed improvements in traditional disease tracking methods, or surveillance. However, let’s consider less obvious methods that could provide valuable information. How can we bring needed innovation to public health disease tracking?

SEWAGE SURVEILLANCE

Largely implemented in the United States during the 1990s to drive the eradication of Polio, many states started surveillance programs that sampled wastewater that entered treatment plants. By sampling wastewater, epidemiologists were able to survey a large population and implement vaccination campaigns in the area to inoculate those who needed it.

These sample principles can be translated to COVID-19 and have been thoroughly tested in the New Haven, CT metropolitan area. Although, instead of wastewater, the involved researchers instead turned to “primary sludge” which is composed of suspended solids and has been shown to contain higher concentrations of pathogens than wastewater because it is relatively undiluted.

The research from New Haven has shown that proactive surveillance of primary sludge can effectively track the presence of COVID-19 in the area. There isn’t a method to quantify the amount of cases relative to the concentration of pathogens in the sludge but it does correlate with rates of hospitalizations and cases in the area. The greatest advantage of sewage surveillance is that public officials can get a sense of epidemiological trends without people individually getting tested. Symptoms and suspected exposure prompt individual tests while sewage can be tested proactively.

These methods can be applied in a variety of settings and population levels. Developed areas have the advantage of more organized sewage systems but in lower and middle income countries with communal latrines and less infrastructure, wastewater surveillance can still give a good rough estimate of prevalence.

KEYWORD SEARCH SURVEILLANCE

In 2008, Google introduced Google Flu Trends. It was a collective intelligence platform that tracked internet searches for flu related symptoms in regions all over the world. In 2010 the platform was able to detect a surge in flu cases in the mid-Atlantic US two weeks prior to the cases being confirmed by tests. However, the platform missed the mark on two occasions. In 2009, it did not predict the H1N1 epidemic and it overestimated cases in the 2013-2014 season by 140%. Google ultimately closed off the platform to the public in 2015 due to poor performance. One disadvantage of tracking the flu is that it shares symptoms with many other acute illnesses which proved to be quite the challenge for their algorithms.

In recent studies, COVID-19 has been shown to be an excellent candidate for predicting clusters because it has unique symptoms, such as loss of taste/smell and blueing of the face in severe cases. A study in Japan that collected anonymized search queries and location information confirmed that they were able to predict increases in cases two days before they were confirmed by tests.

Researchers and local governments are very interested in implementing similar technologies on a small scale for predicting clusters. Many studies are still taking place to optimize keywords, algorithms, and determining how to best approach privacy concerns.

How can we use available data to target those in need of economic stimulus payments?

We have seen that public health crises go hand in hand with economic impact. Many countries have struggled with economic stimulus and it’s often challenging to get aid to the most vulnerable among their populations. In the US, we’ve seen direct payments, decreased interest rates, and increased tax credits. However, in developing countries it has been a challenge to get money into the hands of citizens.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

On top of the challenges like the politics and funding of stimulus packages, most developing nations typically don’t have full financial information for a large portion of their population. These challenges require unique solutions.

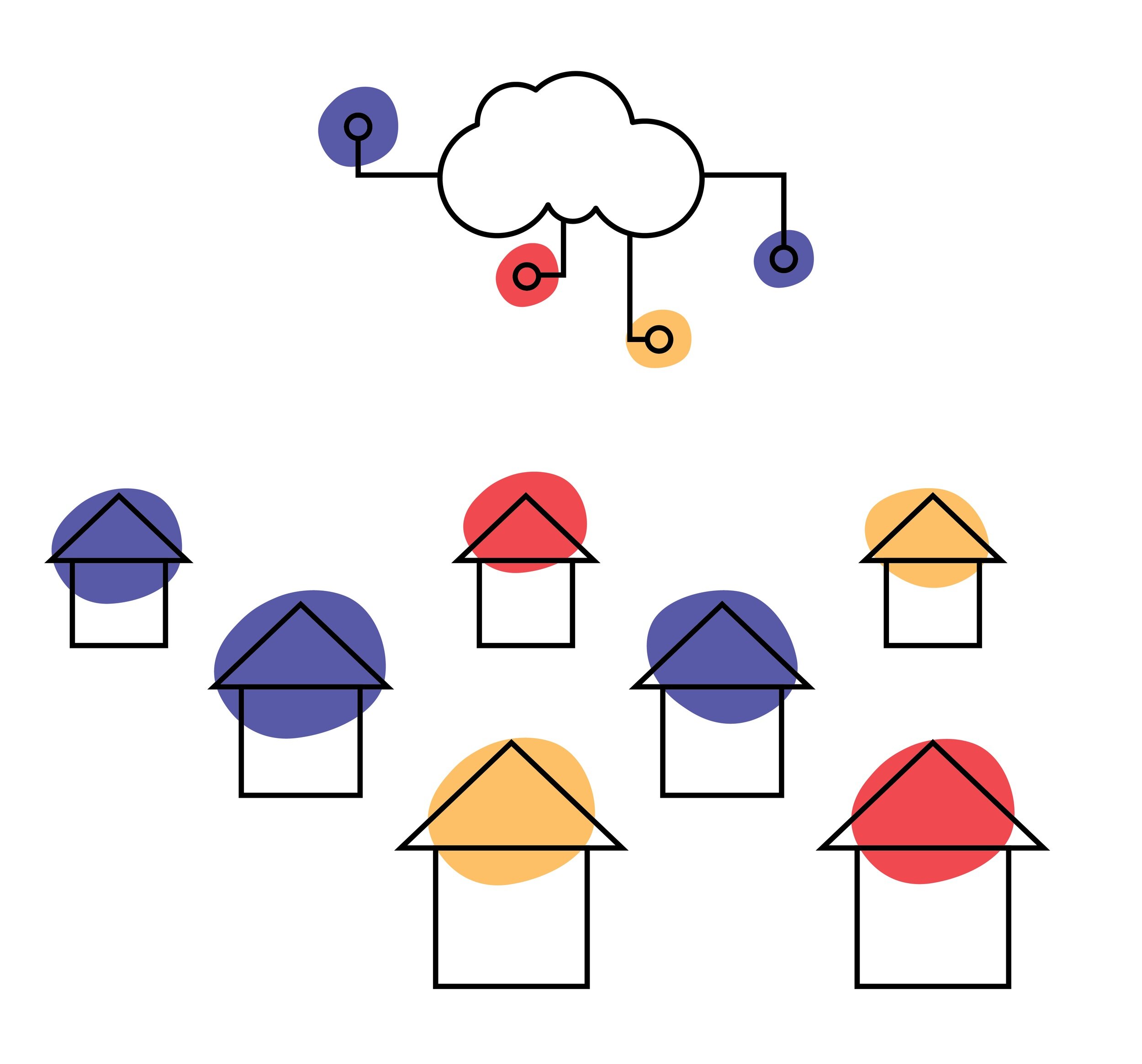

The African nation of Togo partnered with the University of California, Berkeley and a US nonprofit organization called GiveDirectly to address the problems they were facing. They were able to leverage a variety of data sources including econometrics, satellite imagery, and mobile phone data to help reach those most in need. They analyzed their citizens based on formal or informal working conditions, satellite imagery helped determine poorer villages based on roofing materials and lot sizes, and mobile phone data was analyzed for call lengths and distances to determine how much money people were dedicating to their phones.

A basic profile was created using artificial intelligence fed with the variety of data sources. Many farmers and other informal workers that were struck particularly hard by the pandemic were able to secure immediate payments through their cell phones and Togo plans to expand their efforts to more socioeconomic classes.

INNOVATION IN TIMES OF HARDSHIP

Some of the greatest biomedical innovations are the products of global hardships. World War 1 saw the development of modern blood transfusion methods and WW2 ushered in the first generation of antibiotics. With the unfathomable advancement of technology since the 1940s, it is imperative to leverage the tools we have at our disposal to drive innovation and solve problems.

In an ideal world, massive pushes in innovation would be proactive instead of reactive, a slow trickle of advancements instead of a boom. A lot of the data and technology that are being utilized for innovative surveillance and economic solutions were at the disposal of researchers before the pandemic started.

Sources:

Hisada, S., Murayama, T., Tsubouchi, K. et al. Surveillance of early stage COVID-19 clusters using search query logs and mobile device-based location information. Sci Rep 10, 18680 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75771-6

Larsen, D.A., Wigginton, K.R. Tracking COVID-19 with wastewater. Nat Biotechnol 38, 1151–1153 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0690-1

Peccia, J., Zulli, A., Brackney, D.E. et al. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater tracks community infection dynamics. Nat Biotechnol 38, 1164–1167 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41587-020-0684-z

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.